The Wordhord

In Old English, a wordhord was a hoard of words — a store of language kept close, ready to be drawn on when it mattered most. To unlock the wordhord was to begin to speak with purpose and skill.

One of the earliest and most evocative uses comes from Beowulf, just as the hero prepares to speak for the first time:

Him se yldesta andswarode, The eldest of them answered,

werodes wīsa, wordhord onlēac: the leader of the warriors, unlocked his wordhoard:

“Wē synt gumcynnes Gēata lēode “We are men of the Geatish people,

and Hīgeles heoras; Beowulf is mīn nama…” Hygelac’s hearth-companions; my name is Beowulf…”

To open one’s wordhord is not simply to speak — it is to draw on knowledge, memory, and meaning, and shape them into something that can be shared.

This section gathers reflections on the structure, history, and meaning of English words. You’ll find etymology cards, seasonal explorations, and word-family notes that trace how language grows — not at random, but through stories, roots, and sound.

Each entry examines how a word was built, where it came from, and how its meaning has shifted through time, translation, and use. It’s a place for wordcraft grounded in history — practical, curious, and shaped by the belief that language is not just learnt, but forged.

Praise: words that shine with worth

A short exploration of the word ‘praise’, from Latin worth to Greek celebration and Hebrew shining joy, grounded in Luke 2:20.

Heart – a word shaped by courage, thought and feeling

A short exploration of the word ‘heart’, tracing its path from ancient Indo-European roots through Greek kardía to modern English. The post reflects on Luke 2:19 and shows how languages have long used the heart to express the inner life.

Shepherd – a word shaped by flocks and centuries

A short exploration of the word ‘shepherd’, from Old English ‘sceaphierde’ to Greek ‘ποιμήν’ and Latin ‘pastor’. With a photo taken at Cuckmere Haven, this piece follows how a simple pastoral term grew into a rich metaphor across European languages and Bible translations.

Peace: where binding becomes wholeness

A short exploration of the word ‘peace’, from Latin pax and Greek eirēnē to Hebrew shalom, tracing how English came to hold meanings of harmony, safety, and wholeness.

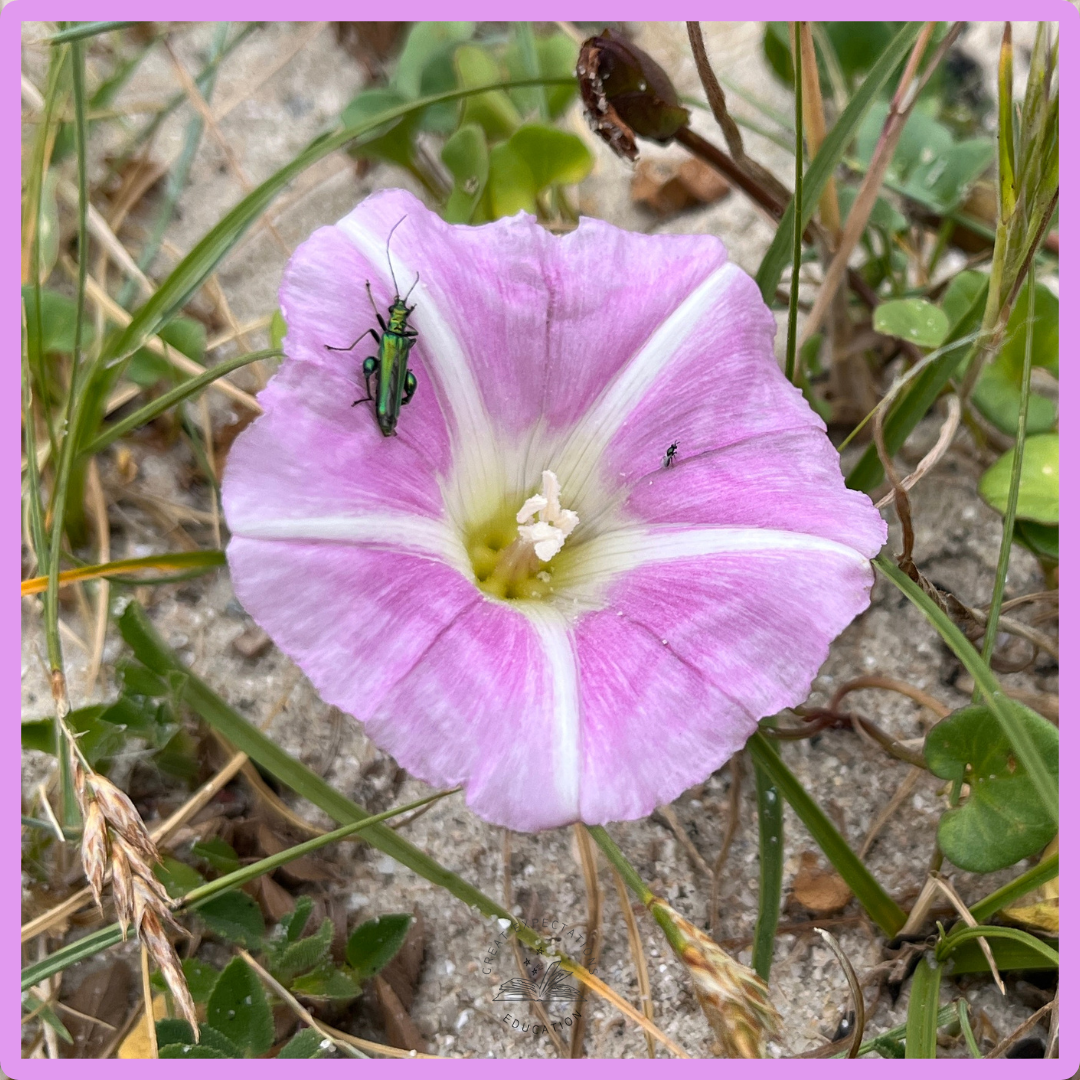

Glory: a word shaped by light and voice

A short exploration of the word ‘glory’, tracing its path from Latin ‘glōria’ and Old English ‘wuldor’ to the brightness and honour found in Luke’s nativity. Featuring a beach morning glory from La Trinité-sur-Mer.

Saviour – a word shaped by rescue and kingship

Luke 2:11 names Jesus as both Saviour and Messiah. This post explores how the word ‘saviour’ travelled from Latin and Greek into English, and how its earlier uses for ancient rulers are reshaped in the New Testament to describe Christ alone. Image taken on the cliffs of Anglesey.

Manger – from Latin chewing to English crib

A manger is a simple feeding trough, shaped by centuries of language change from Latin through French into English. This entry traces its history and links it with an image taken at Whipsnade, where deer gather around a real trough.

Town: the settlement that grew from a fence

A short exploration of the word ‘town’, from Old English ‘tūn’ meaning an enclosed homestead to the Greek ‘polis’ of Luke’s Gospel. The accompanying image comes from Legoland Denmark’s Small Danish Town display, echoing how communities form around shared life.

Census: one mark at a time

A short study of the word ‘census’ in Luke 2, tracing its roots from Roman record keeping to the Greek ‘apographē’. The accompanying image shows a line drawn through homemade gingerbread sensory salt, echoing the act of writing a name into a register.

Blessed – light on the water at Lantic Bay

A word card exploring the history of ‘blessed’ in Scripture, paired with an image taken above Lantic Bay.

Servant: a word shaped by surrender

Explores the long history of ‘servant’, from Latin slavery to chosen devotion in Luke’s Gospel, and how European translations have softened its meaning.

Birth: the story of bearing and becoming

A clear exploration of the word ‘birth’, tracing its history from Old Norse and Proto-Germanic roots to Greek tiktō in Luke 1.31.

Throne: a seat that carries its own story

A look at the long journey of ‘throne’, from Greek ‘θρόνος’ to modern English, with a Viking high seat from Stockholm as the accompanying image.

Sin: a word that never aimed at archery

A short exploration of the English word ‘sin’, its Germanic roots, and how it came to be used in Bible translation. This Word Card also untangles the popular archery misconception and shows how the Greek terms actually work.

Pledge: a word bound by promise

The story behind ‘pledge’, from Germanic guardianship to the Greek and Latin language of binding promise in Matthew 1.18.

Pregnancy: carried before birth

Pregnancy traces back to Latin ‘praegnantia’, meaning ‘carrying before birth’. Other European languages picture the idea through weight, enclosure, and taking together. Greek adds its own structure with ‘syllambanō’.

Perseverance — The Long Race of Hebrews 12

Hebrews 12 describes faith as a long race. This word card explores the history of ‘perseverance’ alongside the Greek term in the passage, paired with an image from Nant Ffrancon Pass that echoes the steady climb of the text.

Righteousness that Stands Straight

A short look at the word ‘righteous’, its Old English and Hebrew roots, and how Scripture uses the idea of the straight and upright way. Written with an orthodox evangelical understanding of God’s justice and Christ’s fulfilment.

Wonderful Counsellor

The phrase ‘wonderful counsellor’ in Isaiah 9 points to the Messiah whose wisdom rises above ordinary human insight. This word card explores the Hebrew ‘pele yo‘etz’, the English forms, and the major European translations that shaped how the title entered English.

Perfect: A Word of Completion

A short exploration of how ‘perfect’ first meant something completed or fulfilled, from Latin and Greek roots to European Bible translations in Hebrews 11:40.