The Wordhord

In Old English, a wordhord was a hoard of words — a store of language kept close, ready to be drawn on when it mattered most. To unlock the wordhord was to begin to speak with purpose and skill.

One of the earliest and most evocative uses comes from Beowulf, just as the hero prepares to speak for the first time:

Him se yldesta andswarode, The eldest of them answered,

werodes wīsa, wordhord onlēac: the leader of the warriors, unlocked his wordhoard:

“Wē synt gumcynnes Gēata lēode “We are men of the Geatish people,

and Hīgeles heoras; Beowulf is mīn nama…” Hygelac’s hearth-companions; my name is Beowulf…”

To open one’s wordhord is not simply to speak — it is to draw on knowledge, memory, and meaning, and shape them into something that can be shared.

This section gathers reflections on the structure, history, and meaning of English words. You’ll find etymology cards, seasonal explorations, and word-family notes that trace how language grows — not at random, but through stories, roots, and sound.

Each entry examines how a word was built, where it came from, and how its meaning has shifted through time, translation, and use. It’s a place for wordcraft grounded in history — practical, curious, and shaped by the belief that language is not just learnt, but forged.

Spaghetti: A Story in Strands

The word ‘spaghetti’ comes from Italian ‘spaghetto’, meaning ‘little cord’. Its ancestor, Late Latin ‘spacus’, referred to a thread or strip. Arab influence in medieval Sicily shaped the early pasta strands called ‘itriyah’, which evolved into the spaghetti we know today.

A Salted Thing

From Roman salt cellars to Italian delicatessens, the word salami has always meant ‘a salted thing’.

Pizza: from Greek ‘pitta’ to global flatbread

‘Pizza’ first appears in a 997 AD Latin charter from Gaeta. Its name may come from Greek ‘pitta’ meaning ‘cake’ or from the Lombardic ‘pizzo’ meaning ‘bite’. In Italian, it once meant any tart or flatbread. The Neapolitan dish of the eighteenth century turned it into the food we recognise today.

Ricotta: from Latin heat to Italian whey

Ricotta comes from Latin recōcta ‘recooked’, describing whey heated a second time to form a fresh curd. This word card traces its path from Roman dairies to modern English.

Mozzarella – a cheese with its name pinched off

The Italian word ‘mozzarella’ means ‘a little cut piece’, from ‘mozzare’, ‘to cut off’. Its root goes back to Latin ‘mutilus’, shared with English ‘mutilate’. From papal kitchens to modern pizza, the name still recalls the motion of a cheesemaker’s hand shaping fresh curd.

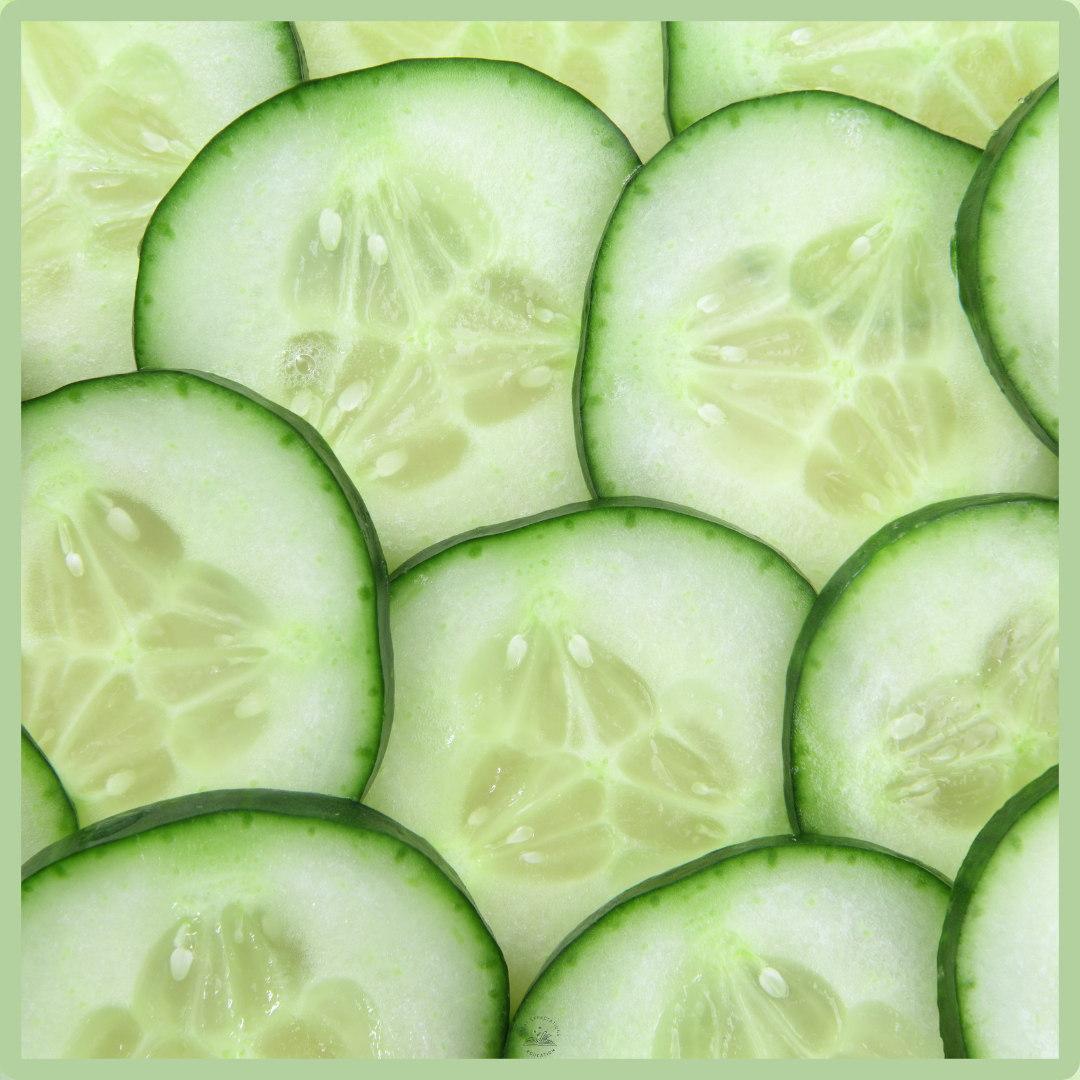

Cucumber – a traveller from Sanskrit gardens to English tables

The cucumber’s name grew from Sanskrit and Latin roots, spreading through French and Greek into Europe’s many languages.

Strawberry – a berry with no straw in it

English alone calls it the ‘strawberry’. Others call it the ‘earth berry’ or the ‘fragrant fruit’. New research traces our word not to straw mulch but to an old European habit: threading wild berries onto a straw of grass.

Shine: the long story of brightness and becoming light

A short exploration of the word ‘shine’, from Old English ‘scinan’ to the Hebrew forms behind Isaiah’s ‘arise, shine’. This study traces how English, Hebrew and European translations express radiance, brightness and becoming light.

Dream: a word that drifts between joy and revelation

A short exploration of the word ‘dream’, from its Old English meaning of joy to its role in Matthew’s Gospel as ‘onar’, a dream sent from God.

Gift: a word shaped by giving

Luke 2:11 names Jesus as both Saviour and Messiah. This post explores how the word ‘saviour’ travelled from Latin and Greek into English, and how its earlier uses for ancient rulers are reshaped in the New Testament to describe Christ alone. Image taken on the cliffs of Anglesey.

Star: a word scattered across the skies

A brief look at how English ‘star’ traces back to the ancient Indo-European root meaning ‘to scatter’. Greek ‘astēr’, Latin ‘stella’, and Germanic ‘steorra’ all reflect the same image: points of light spread across the sky, guiding travellers long before the Magi followed the rising star.

Worship: from worth-ship to bowing low

A short look at the word ‘worship’, from Old English ‘worth-ship’ to the Greek ‘proskyneo’. Across Europe the word carries ideas of worth, direction and bowing low.

Thanks: a word shaped by thought and grace

Explores the deep history of ‘thanks’, from Germanic thought to Greek grace, anchored in Luke 2:36 to 38.

Light: a word that opens the eyes

A short exploration of the word ‘light’ from Old English ‘leoht’ to the Greek φῶς (phōs) of Luke 2:32. This piece traces how languages across Europe speak of brightness, clarity, and revelation, and how these ideas have shaped English over time.

Praise: words that shine with worth

A short exploration of the word ‘praise’, from Latin worth to Greek celebration and Hebrew shining joy, grounded in Luke 2:20.

Heart – a word shaped by courage, thought and feeling

A short exploration of the word ‘heart’, tracing its path from ancient Indo-European roots through Greek kardía to modern English. The post reflects on Luke 2:19 and shows how languages have long used the heart to express the inner life.

Shepherd – a word shaped by flocks and centuries

A short exploration of the word ‘shepherd’, from Old English ‘sceaphierde’ to Greek ‘ποιμήν’ and Latin ‘pastor’. With a photo taken at Cuckmere Haven, this piece follows how a simple pastoral term grew into a rich metaphor across European languages and Bible translations.

Peace: where binding becomes wholeness

A short exploration of the word ‘peace’, from Latin pax and Greek eirēnē to Hebrew shalom, tracing how English came to hold meanings of harmony, safety, and wholeness.

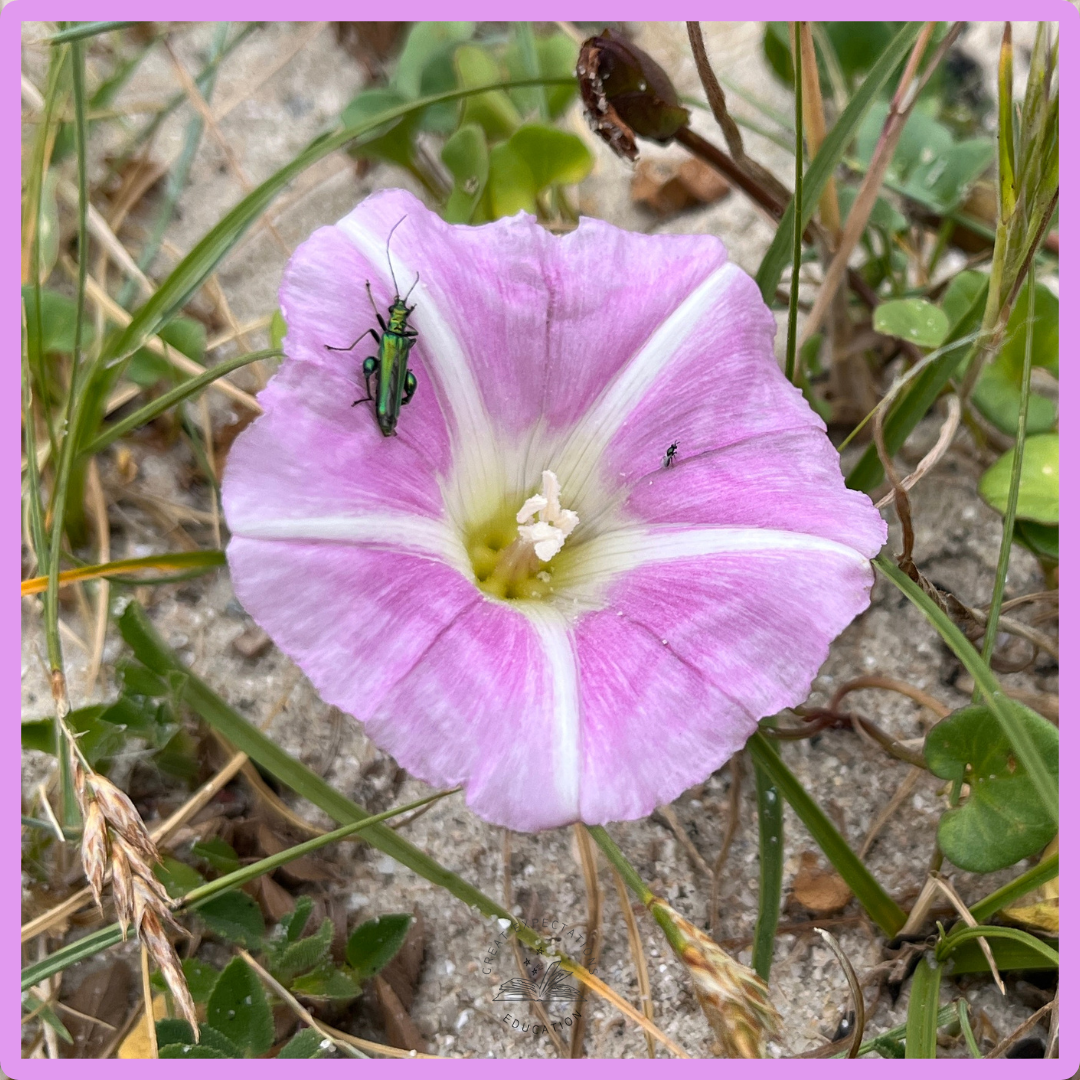

Glory: a word shaped by light and voice

A short exploration of the word ‘glory’, tracing its path from Latin ‘glōria’ and Old English ‘wuldor’ to the brightness and honour found in Luke’s nativity. Featuring a beach morning glory from La Trinité-sur-Mer.

Saviour – a word shaped by rescue and kingship

Luke 2:11 names Jesus as both Saviour and Messiah. This post explores how the word ‘saviour’ travelled from Latin and Greek into English, and how its earlier uses for ancient rulers are reshaped in the New Testament to describe Christ alone. Image taken on the cliffs of Anglesey.